Read the latest Vetora news and find handy animal resources here.

Our Vetora team is committed to delivering exceptional, client‑focused care across all eight of our Waikato clinics. If you have any concerns this summer — big or small — we’re always happy to help.

Book an appointment or contact your nearest clinic anytime.

Pets

Summer in New Zealand is a wonderful time to explore the outdoors with your pets—but our hot, humid weather also brings a serious risk: heatstroke. Heatstroke in dogs and cats is a life‑threatening emergency where body temperature rises dangerously above 40°C and organs begin to fail. Quick action can save a life.

This guide explains the early warning signs, severe symptoms, first aid steps, and simple prevention tips to help keep your pets safe through the warmer months.

Recognising heatstroke early can prevent a medical emergency. Watch for:

If you notice any of these, act fast—move your pet to a cooler environment and contact your vet.

Heatstroke can escalate rapidly. If your pet shows any of the following symptoms, this is an emergency:

Immediate veterinary treatment within 90 minutes leads to the best outcomes.

While organising emergency veterinary help, take these steps:

Get your pet into shade or an air‑conditioned space as quickly as possible.

Use cool, damp cloths on the paws, groin, and belly. A fan can also help.

Avoid ice‑cold water or wrapping in large wet towels, as this can trap heat.

Provide small sips of cool water—but never force drinking.

Call your local veterinary clinic or emergency vet while cooling your pet and continue cooling during transport.

Heatstroke is preventable with a few simple precautions:

In a New Zealand summer, the inside of a parked car can reach over 50°C in under 15 minutes, even in the shade and with windows cracked. This is deadly for pets and can cause irreversible heatstroke very quickly.

By recognising the early signs of heatstroke and taking simple preventative steps, you can help ensure your pets enjoy a safe, happy Kiwi summer. If you ever suspect heatstroke, always call your vet immediately—rapid action saves lives.

Pets

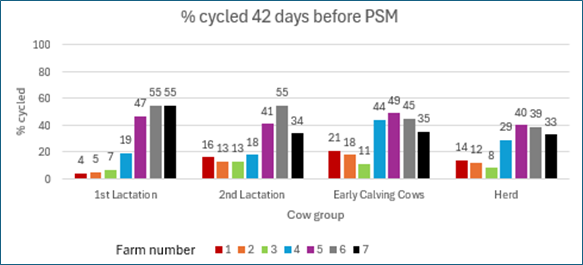

Wearable technology is transforming herd management, but the real power lies in how you use the data. At Vetora, we help farmers turn insights into action—starting with pre-mating heat detection up to 42 days before mating begins.

Recent data from seven Waikato farms shows a wide variation in pre-mating cycling rates. For example, Farm 1’s first-lactation cows were only 4% cycled, compared to 16% for second-lactation cows. Meanwhile, Farm 7 had 55% of first-lactation cows cycled versus 34% for second-lactation cows. Why such differences? Every farm has unique factors, and the solutions need to be tailored.

By analysing your wearable data, we can identify these gaps early and create a plan to improve reproductive performance. Better data means better decisions—and better results for your farm.

Ready to make your data work harder? Contact Vetora today and let’s boost your herd’s performance.

Farming

As we head into summer, it’s time to plan ahead for your herd’s health and productivity. Here are key steps for cows, heifers, and calves to keep your farm running smoothly.

Look after yourselves in the sun, and hopefully, you get a well-deserved break off-farm. Wishing you a safe and happy Christmas and New Year!

Farming

Liver Abscess in Heifers: What Waikato Farmers Need to Know

In September, a sick R2 heifer was reported in Otorohanga after rapid deterioration. Despite initial treatment with Engemycin and B12/Selenium, her condition worsened to the point she couldn’t walk back to the yards.

A post-mortem revealed severe emaciation and multiple encapsulated liver abscesses, some up to 6cm in diameter. One abscess had ruptured near the liver’s main blood supply, causing localised peritonitis and a toxic reaction that led to her decline.

Liver abscesses can occur in any age or breed of cattle but are most common in feedlot or grain-fed animals. The primary cause is rumen acidosis, often triggered by a sudden diet change from roughage to high-grain feed. Other causes include:

The bacteria responsible, Fusobacterium necrophorum, proliferates when the rumen lining becomes inflamed, allowing bacteria to enter the bloodstream and seed in the liver.

These heifers had been fed meal during winter, making rumen acidosis the likely cause. In most cases, liver abscesses remain small and only reduce growth rates. However, when an abscess ruptures near major blood vessels, it can cause rapid deterioration and death.

This case highlights the importance of careful feed management to prevent liver abscesses and protect herd health.

Farming

Horn Management in Waikato Dairy Farming: Why It Matters

Horns are permanent pointed growths made of a bony core covered by a keratin sheath, similar to a fingernail. They grow from a coronary ring on the head of cattle and continue throughout the animal’s life. While horns serve natural purposes - such as social status, communication, defence, and even thermoregulation - in modern intensive farming systems, they create significant welfare and safety challenges.

In close-contact environments like milking yards or feed pads, horns can cause injuries to other cows, bruising during transport, and even harm to humans. Common issues include:

One of the most common procedures in spring is disbudding dairy replacement calves at 3 - 6 weeks old. Under Animal Welfare Regulations, this must be done with local anaesthetic before using a hot iron to cauterise the horn growth ring. Older animals with large or deformed horns may require dehorning, which is more complex and often involves sedation and local anaesthetic.

Horn growth is controlled by genetics. A dominant gene produces polled (hornless) cattle, while a double recessive gene results in horned animals. Many beef breeds like Angus and Hereford have been selected for polled genetics. Using these bulls over dairy cows can significantly reduce the need for disbudding.

The challenge: Invest in polled dairy genetics. Within a few years, your herd could be entirely polled, improving welfare and reducing risk for both animals and people.

Farming

Parvovirus is a highly infectious and often deadly virus that mainly affects puppies and unvaccinated dogs. It is resistant to normal disinfection and can survive in the environment for months to years, depending on humidity and temperature.

Some dogs may be subclinically infected, meaning they carry the virus without appearing sick—making it easy to spread. It only takes a tiny amount of virus to infect a new host.

How It Spreads:

The virus is shed in the faeces of infected dogs, and symptoms usually appear 3–7 days after infection.

Parvovirus attacks:

Without treatment, the mortality rate for puppies is around 91%.

If you notice any of these signs, contact your vet immediately—early treatment greatly improves survival chances.

Vaccination is the safest way to protect your pet. Adult dogs rarely get Parvo thanks to widespread vaccination, but yearly boosters are often recommended during annual check-ups.

✅ Check your pet’s vaccination status for Parvovirus, Kennel Cough, and Canine Distemper.

✅ If you’re unsure, call your local vet clinic—we’re happy to help.

✅ Share this post to protect other pets in your community.

📞 Talk to us today about protecting your pet from Parvo!

Pets

Wishing you a successful end to mating and a healthy, productive season ahead.

Farming

Amino acid nutrition in dairy cows is a critical component of optimising milk production, reproduction, and metabolic health. In New Zealand, the challenge lies in balancing amino acids within high-protein, grass-based systems, which differ significantly from the Total Mixed Ration (TMR) systems used in other parts of the world.

Proteins are made up of amino acids (AAs), and 10 of these are essential—meaning they cannot be synthesised by the cow and must be obtained through the diet. Among these, methionine (Met) and lysine (Lys) are typically the first- and second-limiting amino acids in dairy cow diets. When deficient, they can restrict protein synthesis, even when dietary crude protein (CP) is sufficient.

Imbalanced amino acid profiles can:

To provide methionine and lysine in New Zealand dairy systems, farmers can use rumen-protected (bypass) amino acid products. These are formulated to withstand ruminal digestion and be absorbed in the intestine.

When selecting products, it’s important to consider:

These factors help determine the appropriate supplementation levels.

Supplementing amino acids is not just about quantity—it’s also about the correct ratio. A lysine-to-methionine ratio of approximately 3:1 in the metabolizable protein (MP) is often considered ideal for milk protein synthesis.

In practical terms, some trials have used:

It is advisable to supply methionine and lysine during critical physiological periods, such as:

Farming

Earlier this year, our veterinary team was called out to a Waikato dairy farm after a group of cows broke into a stack of mouldy maize. A few days later, several cows began showing signs of illness, prompting an urgent on-farm visit.

One cow was found down in the paddock, displaying concerning symptoms:

We immediately administered supportive care, including:

Meanwhile, other affected cows remained standing but presented with:

Given the recent maize consumption, rumen acidosis was a primary suspect. However, we also considered:

To confirm the diagnosis, we collected faecal samples for laboratory testing.

Both rumen acidosis and Salmonella can cause foul-smelling diarrhoea. However, there are key differences:

Regardless of the cause, fluid therapy with electrolytes is essential to replace losses and support recovery.

Lab cultures confirmed the presence of Salmonella. Interestingly, the strain identified in this outbreak was Salmonella Give, while the previous outbreak had been caused by Salmonella Typhimurium. This indicated two separate outbreaks, not a continuation of the same infection.

Given the recurrence, we recommended vaccinating the herd. Although the vaccine does not currently include the Salmonella Give strain, which is relatively new, there may be some cross-protection. Vaccination during an outbreak is still considered beneficial to limit spread and protect unaffected animals.

To reduce the risk of Salmonella outbreaks in your herd:

This case highlights the importance of early intervention, accurate diagnosis, and proactive prevention in managing herd health. If you suspect a Salmonella outbreak or have concerns about feed safety, contact our veterinary team immediately.

Farming

Has your dog injured their knee joint, just like Damian McKenzie? In dogs, this common injury is a tear or rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) — the veterinary equivalent of the human ACL.

The cranial cruciate ligament is one of two key ligaments in a dog’s knee (stifle) joint. It stabilises the joint and prevents internal rotation. Damage to the CCL is one of the most common causes of hind leg lameness in dogs across all breeds and sizes — not just active or athletic dogs.

If your dog has torn their CCL, surgical repair is usually required. Cage rest may help very small dogs, but it’s rarely effective for medium to large breeds.

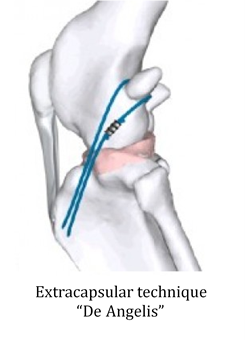

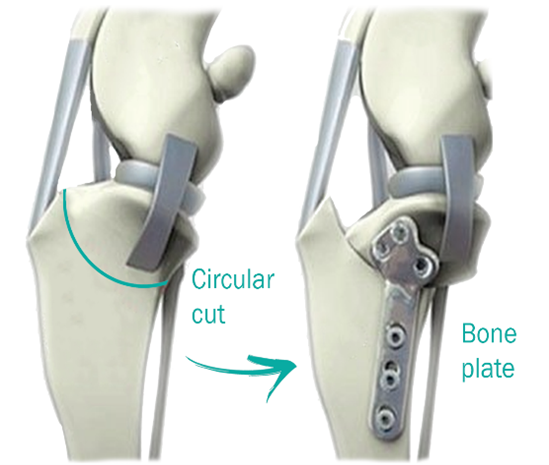

At Vetora Hamilton, we offer two trusted surgical options to stabilise your dog’s knee and restore mobility:

This extra-articular procedure uses a suture to mimic the function of the CCL and stabilise the joint.

✅ Best suited for small to medium-sized dogs

💰 Cost: $1,800 – $2,200

Recommended by most orthopaedic specialists, TPLO involves reshaping the tibia to change joint loading and allow normal weight-bearing.

✅ Ideal for active or larger dogs

💰 Cost: Approx $4,800

These advanced cruciate surgeries are offered exclusively at our Hamilton clinic, serving pet owners across the Waikato region — including Te Awamutu, Cambridge, Morrinsville, Otorohanga, Putaruru and surrounding communities.

📍 Book your dog’s cruciate surgery at Vetora Hamilton today

📞 Call us or book online to get your pet back on their feet for summer!

Pets

Lameness is a year-round challenge, but late spring can be particularly tough for Waikato and Taupō dairy farmers. With mating season approaching, lame cows can cause:

Before the rush of mating, take time to reduce lameness issues and keep your herd moving.

Early identification of lame cows is key to faster recovery and better animal welfare. Hoof problems often start small and worsen over time. If you catch and treat them early:

Tip: Train farm staff to check for lameness every time cows walk to and from the shed. Mark and draft affected cows promptly for examination.

When treating a lame cow, the most important step is to lift the foot and inspect it. Skipping this step and going straight to antibiotics can:

Most lame cows do not need antibiotics. Common causes in NZ include:

Only digital dermatitis and foot rot consistently require antibiotics. The rest can often be treated with hoof trimming, pain relief, and time.

Learning to diagnose and trim hooves is a valuable skill. Our Taupō veterinary team can:

Contact your local Waikato or Taupō vet clinic for advice, treatment, or to book a training session.

📞 Call us today – let’s keep your cows moo-ving this season!

Farming

When a farmer in Tokoroa, Waikato called about a five-week-old Friesian cross Jersey calf with a “blimp-sized” abdomen, our team knew immediate action was needed. The calf had:

These signs indicated significant pain and possible gastrointestinal complications.

We passed a stomach tube to rule out oesophageal impaction and relieve any free gas. The tube entered the rumen easily, eliminating an oesophageal blockage. Only a small amount of gas was released, ruling out free gas bloat. Green liquid in the tube also ruled out ruminal milk drinking bloat.

We opted for conservative treatment:

The calf improved overnight, and the bloating reduced significantly. The most likely cause was:

If you suspect bloat in calves, call your local Waikato vet clinic immediately. Early intervention saves lives.

📞 Contact us today for advice or emergency support.

Farming

When it comes to drenching calves for worms and managing coccidiosis, timing is everything. But in New Zealand—especially here in the Waikato—there’s still a lot we don’t know about the best time to start.

That’s why this spring 2025, our veterinary team is launching a regional study to help answer some of the most common questions we hear from local farmers:

We’re inviting farmers across the Waikato to participate in a collaborative study aimed at improving calf health and parasite management. As part of our Lepto vaccination visits, we’ll:

You’ll receive a personalised report with your farm’s results, and we’ll compile anonymised data across all participating farms to identify trends and best practices.

By participating, you’ll help us answer key questions and improve parasite control strategies for the entire region. The benefits include:

If you’d like to be part of this important study—or if you just want to chat about your calf drenching programme—we’re here to help.

📞 Contact your local clinic today to get involved or learn more.

Together, we can build a healthier future for our calves and our communities.

Lifestyle

Farming

With a wide range of drenches available on the market, choosing the right one for your calves isn’t just a matter of preference—it’s a critical decision that can significantly impact their health, growth, and long-term productivity.

Drenching plays a vital role in calf rearing. Worm infestations can reduce growth rates by up to 30%, primarily due to appetite loss and poor nutrient absorption. Common symptoms include:

Unchecked worm burdens can escalate into serious conditions such as parasitic gastroenteritis, bronchitis, or pneumonia—especially when lungworm is involved.

From weaning through to around 15 months of age, calves are particularly susceptible to parasites. Their immune systems are still developing, leaving them less equipped to fight off infections. This makes early and effective parasite control essential.

When it comes to young stock, quality should never be compromised. High-quality drenches are backed by:

In contrast, cheaper drenches may result in:

Saving a few dollars upfront can lead to long-term losses in productivity and animal health.

Purchasing your drench through your veterinarian ensures you receive expert, tailored guidance. Vets consider:

They can also help you:

Veterinary support is not just about choosing a product—it’s about building a sustainable parasite control strategy. This is crucial for:

Lifestyle

Farming

Farming

Synchronising heifers isn’t for everyone – it’s a lot of extra work at a busy time of year. But the economics of getting extra replacement heifer calves from your highest BW animals and increased days in milk do make it worthwhile, if you decide to do it.

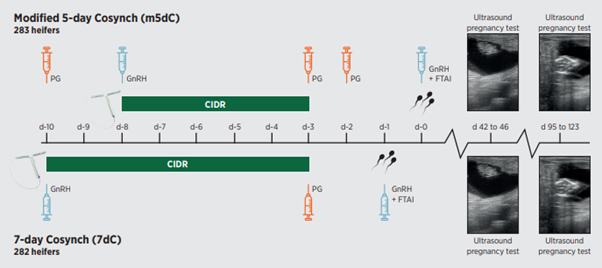

There are several synchronisation programmes available for dairy farmers in the Waikato region. While many have been used for years, the Modified 5-Day Cosynch Programme shows significant improvements over the standard heifer CIDR synchrony programme, the 7-day Cosynch.

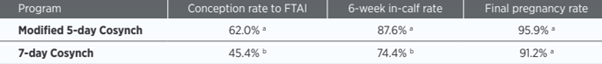

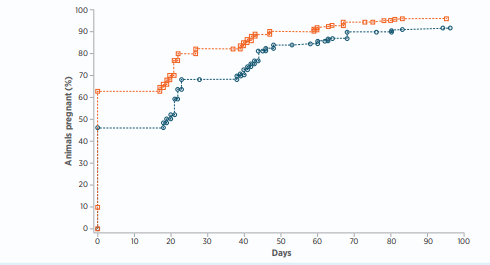

Looking at the table and graph below, there is an increase in conception rate to AI from 45.5% with the standard programme to 62% with the modified 5-day Cosynch.

The downside (there is almost always a downside) is 5 yardings during the 10 days of the programme, compared to 3 yardings for the old programme. There is also an increase in cost for the extra 2 PG injections. The table below shows the timing of both programmes.

There are a couple of other options for synchronising heifers that don’t involve CIDRs. They are:

If you're considering heifer synchronisation in Waikato, King Country, or surrounding areas, contact your local Vetora clinic. Our experienced veterinary team can help you choose the most effective and cost-efficient programme for your herd.

Farming

A two-year-old Friesian cross steer in the Waikato region recently presented with lameness in his right hind leg. The steer was part of a mob of twelve similar age steers that had arrived on the property as yearlings. Upon examination, the steer showed inflamed, thickened skin between the heel bulbs. There was no interdigital footrot between the claws - leading to a diagnosis of Bovine Digital Dermatitis (BDD).

BDD is a contagious bacterial infection caused by Treponema species. It’s the most important infectious cause of lameness in cattle worldwide, first identified in Italy in 1974 and diagnosed in New Zealand dairy herds in 2004. Since then, it has spread across all major dairy regions, including Waikato and King Country. One study in Taranaki found 2/3 of 224 herds examined had at least one cow with BDD.

BDD typically affects the back feet and causes damage to the skin between the heel bulbs or along the coronary band.

Wet, muddy conditions—common in the Waikato region—combined with faecal contamination on races, yards, and feedpads, significantly increase the risk of infection. Infected cattle can spread BDD quickly, making quarantine and biosecurity essential and checking stock before arriving on-farm are useful preventative measure.

In the case above, the steer was treated with:

Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent herd-wide outbreaks.

To reduce the risk of BDD on your farm:

If you're farming in Ōtorohanga, Te Awamutu, Putaruru, Tokoroa, Cambridge, Hamilton, or anywhere in Waikato or King Country, contact your local Vetora clinic. Our experienced vets can help you:

Farming

Weaning is a pivotal stage in calf rearing that directly influences lifetime performance. For farmers across Waikato and King Country, successful weaning requires more than just removing milk—it demands careful attention to nutrition, rumen development, parasite control, and stress management.

Weaning should be based on liveweight and rumen development, not age alone.

High-quality calf meal or pellets rich in starch and protein stimulate rumen papillae growth, improving nutrient absorption.

Ensure calves are confidently eating pasture and meal before weaning.

Look for:

Water is vital for rumen function and overall calf health.

Ensure constant access to clean, fresh water.

Calves are highly susceptible to worm burdens after weaning.

Young calves need leafy, high-energy pasture—not mature or fibrous grass.

This supports continued growth and development.

Handle calves calmly and keep groups stable.

Avoid weaning during poor weather or feed shortages.

Successful weaning is about more than just removing milk.

Balancing nutrition, parasite control, and stress management—along with proper weight and rumen readiness—ensures calves transition smoothly and continue on a path to strong lifetime productivity.

Well-grown heifers make well-grown cows.

Whether you're farming in Te Awamutu, Ōtorohanga, Putaruru, Tokoroa, Cambridge, Hamilton, or surrounding areas, your local Vetora clinic is here to support your calf rearing success. Contact us for tailored advice, drenching plans, and growth monitoring tools.

Farming

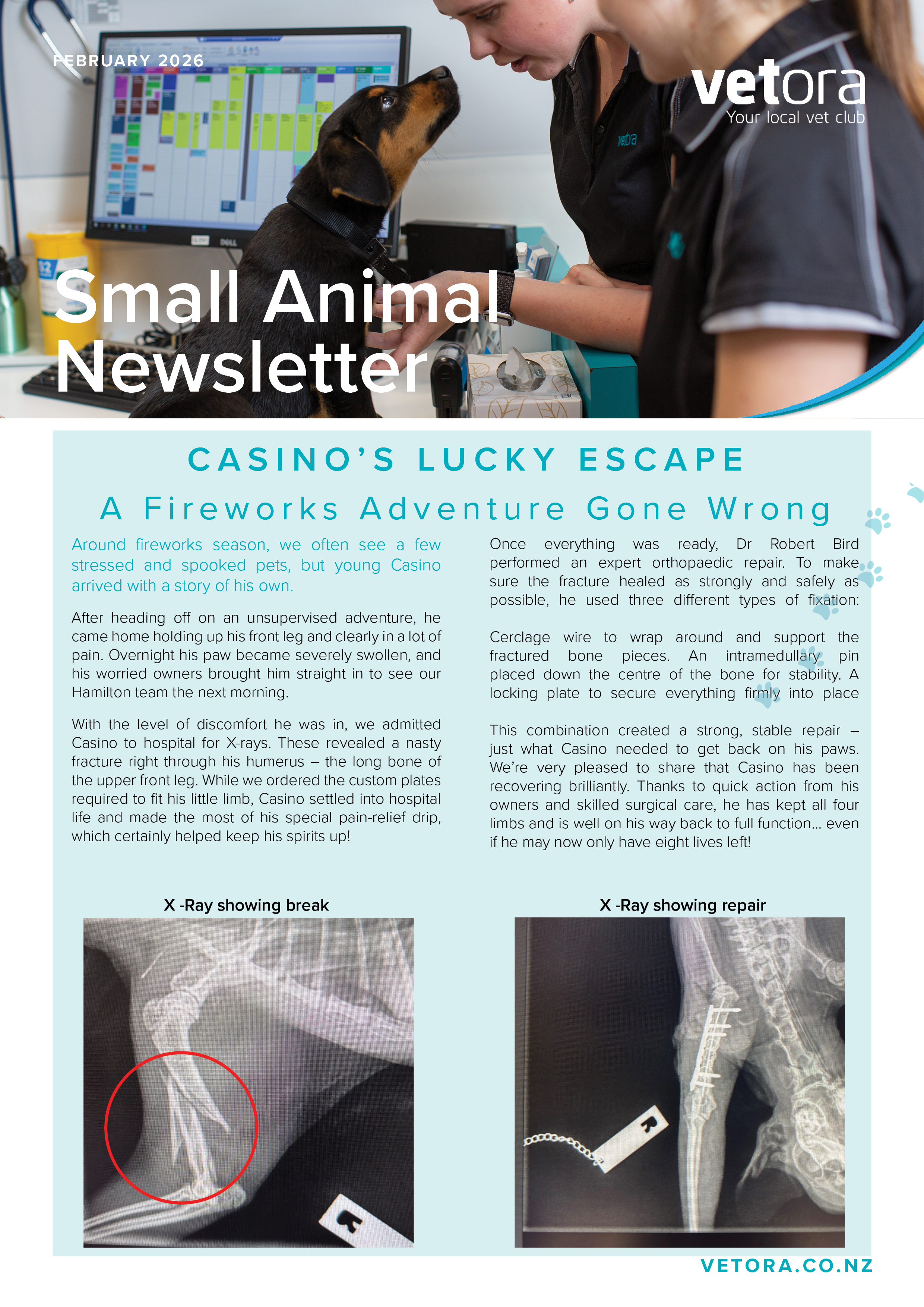

We’re excited to share the latest edition of our quarterly Small Animal Newsletter, packed with updates, insights, and a few treats for our pet-loving community!

Here’s what you’ll find inside this issue:

Take advantage of our current promotions on selected products and services – perfect for keeping your furry friends happy and healthy as we head into the new season.

This quarter’s spotlight dives into a fascinating case from one of our clinics, showcasing the teamwork, diagnostics, and care that go into helping our patients thrive.

Get to know one of our amazing team members! We love introducing the people behind the scenes who make our clinics such a special place for pets and their owners.

Thank you for being part of our community – we’re proud to serve the pets and people of the Waikato with care, compassion, and clinical excellence.

Pets

We’re pleased to share the latest edition of our monthly Focus on Dairy newsletter, created especially for our farming community across the Waikato.

This month’s issue is packed with valuable insights and practical updates, including:

A real-world example from one of our production animal vets, highlighting diagnostic challenges and treatment outcomes on-farm.

Take advantage of current offers on selected products and services to support herd health and farm efficiency.

Stay informed with the latest developments in dairying – from seasonal herd management tips to emerging technologies and best practices.

Whether you're a long-time client or new to our clinics, Focus on Dairy is designed to keep you connected, informed, and supported in your day-to-day operations.

Thanks for being part of our farming community – we’re proud to support the people and animals that power the Waikato.

Farming

One Thursday afternoon in September, I was called out to see a cow in distress. She was down in the yard, groaning, and severely bloated—so much so that I feared she might die from bloat right in front of me.

My first priority was to relieve the gas pressure in her rumen. After confirming it was free gas with a needle (a continuous hiss confirmed this), I administered a local anaesthetic and inserted a red plastic trocar. The gas released quickly, but the cow still looked unwell.

I began a full clinical exam. She was due to calve in about five days, and my checks confirmed the calf was still alive. Suspecting a possible blockage, I passed a stomach tube, which went down easily—ruling out an obstruction. However, the cow reacted poorly, groaning and rolling, which added to the puzzle.

As I stood back and reassessed, her symptoms—bloat, weakness, and depression—pointed to hypocalcaemia (milk fever). It was unusual to see such extreme bloat with milk fever, especially in a cow that hadn’t calved yet. Still, I decided to administer intravenous calcium.

The response was almost immediate. Her condition improved visibly during the infusion, and she was up and walking not long after I left. A few days later, she calved a healthy calf.

Thanks to Cow Manager wearables on this farm, we could review her activity data. The day before the incident, she hadn’t eaten or moved much—clear signs of early illness. This lack of intake during the critical transition period likely triggered the milk fever, even before calving.

This case was one of the most unusual presentations of milk fever I’ve seen—but with quick action and the right diagnosis, it had a successful outcome.

Farming

Calves are creative creatures, and anyone who has done calvings knows they can find any number of interesting positions to cause a problem to the cow when they enter the world. Occasionally though, the issue lies not with the calf itself, but actually with the uterus.

Uterine torsions occur when the body of the uterus twists around at the level of the cervix and can range from 90 to 360 degrees. The twist both narrows the birth canal, and prevents the cervix from dilating properly. Cows with a uterine twist are basically stuck in stage 1 of labour (cervical dilation) and will not be able to progress to stage 2 (birth of the calf) until the twist is corrected.

In a partial or “open” twist, the cervix will be partially dilated, and you will be able to feel the calf. However the calf will often be either on its side or upside down. The twist may be difficult to distinguish from a poorly dilated cervix, but you may find that your arm drops away to the left or right as you enter the cow. These cows can often be untwisted standing, your vet may untwist them by hand, or using a Gyn stick or torsion rod.

In a complete or “closed” twist, the uterus has twisted down to a complete closure, which can easily be confused with a closed cervix. Cows with a twist of this severity either need to be cast and rolled (essentially rolling the cow around the calf) or have a c section. The key to a successful roll is having plenty of hands to help.

Once untwisted, the next problem to tackle is a poorly dilated cervix. Think of the calf as a loaf of bread, the uterus as a bread bag, and the cervix as the bread tag. Even if you untwist the bread bag, you can’t get to the bread without removing the tag! In a live or freshly dead calf, there is often a good chance the cervix will dilate. With a rotten calf, the chance of dilation is very low and prognosis is poor.

Always consider the possibility of a twisted uterus if a cow is not progressing as quickly as you expect. These cows will not tend to visibly strain or push because the calf is not able to enter the birth canal. Early detection and correction will always give the best chance of a good outcome.

Farming

A bone sequestrum is a portion of dead bone which generally occurs due to direct trauma to bone. Bone sequestrums are not very common and can be seen 2-3 weeks after injury.

How they do they occur?

Direct trauma damages cortical bone (outer layer of bone) which causes bone death due to loss of blood supply and bacterial infection.

What does it look like?

The animal may show mild to moderate lameness. They are often non-healing wounds which can respond to antibiotics but recur once the antibiotic course ends. We often see pus coming from a small drain hole on the leg wound.

How is it diagnosed?

History of trauma, draining tracts and non-healing wounds. We can also ultrasound or radiograph the leg to identify damaged bone.

- Radiograph: Abnormal bone circled.

- Ultrasound: Normal, smooth bone (white curve) is displayed on the left. Sequestrum is displayed on the right where the bone is interrupted (red arrow).

How do we treat this?

Surgery is required to remove the damaged portion of bone. Without surgery, the dead bone acts as foreign material causing a persistent source of irritation and infection

Farming

Farmers are familiar with the common presentation of abscesses as the cause of rapidly growing masses on their cattle, but not all are as they seem. It is important for abscesses to be diagnosed and treated properly. This may include a needle aspirate to confirm pus is present, local anaesthetic to provide pain relief, thorough cleaning of the skin before incision, stand back for a fountain of pus and a good flush, finishing up with the old faithful- blue spray. Antibiotics are not usually required.

This case involved a call for a lump with quite a different outcome. This heifer had a small lump (golf ball sized) as an R1, that was presumed to be a small abscess and left to heal. The lump had stayed the same size for a while, and then in the last 3 weeks or so (as an R2 heifer) had rapidly grown.

The Friesian heifer had a mass on her shoulder, approximately the size of a soccer ball on presentation. As she came through the yards the skin split to reveal bleeding, shiny black tissue. The appearance indicated that the mass was in fact a melanocytoma- a tumour of pigment producing cells. These tumours can grow to impressive sizes and are unable to be transported to the works if the skin is split, which they are prone to doing.

The heifer was prepared for surgery- clipped, cleaned and local anaesthetic ring block applied. The tumour was cut off, sewn up, then pain relief and antibiotics were given to the heifer. At that point she looked brand new but be warned, this surgery can create a blood bath! Sutures were removed after 14 days, she recovered well and was still in calf.

Melanocytomas are an uncommon cancer of cattle (about 5% of all cancers in bovines) and occur usually in young animals. Dark coloured breeds e.g. Angus, Friesian etc are especially prone. Most melanocytomas in cattle are benign, and surgical excision is curative. Approximately 20% of cases may feature spread to lungs or lymph nodes. These tumours are prone to bursting open which then means the animal is unsuitable for transportation to the works. They are often very vascular (can contain abnormal blood vessels) which in rare cases can result in huge blood loss. Surgery is the only curative option, with wide surgical margins the prognosis is good, recurrence is possible but uncommon.

Farming

The transition period is defined as the timeframe from 4 weeks before calving until 4 weeks after calving and is characterised by an increased risk of disease. The changes in metabolic status have a long-term effect on the health, fertility and productivity of dairy cows. Most metabolic conditions, such as milk fever, ketosis, primarily affect cows during this period as do disorders such as RFMs, metritis, displaced abomasum and lameness.

Feed intake and nutrient density of the diet determine the nutrients available to the cow and developing foetus, so cows need enough energy for them and the foetus. During the last month of gestation cows (550kg bodyweight) should be provided with at least 8 to 10 kg DM in feed, providing at least 10 MJ/kg DM, to allow for foetal growth without depletion of the cow’s body stores. Over feeding cows prior to calving can predispose cows to milk fever, udder oedema and mastitis.

It is recommended that cows are dried off in the BCS they are required to calve. A BCS 5 for cows, 5.5 for heifers are considered optimum to achieve the best results in terms of subsequent production and reproduction. Cows at or above target BCS should be fed 90 percent of their daily energy requirements for two to three weeks before calving. Cows that are below target BCS should be fed 100 percent of their daily energy requirements.

The management of the transition diet is important to reduce the risk of milk fever. Pastures high in potassium and sodium should be limited due to their detrimental effect on the DCAD, so avoid access to effluent paddocks. Adequate magnesium and phosphorus also need to be provided in the late dry period.

There are a range of ways to supplement with magnesium – magnesium oxide can be mixed in feed or dusted on pastures; magnesium sulphate and magnesium sulphate can be added to the drinking water. Cows need to adjust to treated water - so slowly introduce it, as high levels make the water unpalatable. Also, magnesium intra-ruminal bullets can be used - they release magnesium over 9-12 weeks.

Dairy cows have a level of immunosuppression due to the period immediately before, during and after calving. This means they are more susceptible to disease, and this can be made worse by inadequate trace element nutrition. Aim for optimal levels of selenium, copper, and zinc.

The goals of nutritional and environmental management during the transition period are to maximise the appetite of the cow just before and after calving, minimise body fat mobilisation around calving, maintain calcium at and after calving, and to maintain or enhance the animal’s immune function.

Farming

As the colder months settle in, it’s not just us feeling the chill — our pets do too!

You might notice your furry friends slowing down a little more than usual.

Stiffness, moving slower

Reluctance to move, climb stairs

Repeatedly licking at joints

Just seeming a bit “off”

These can all be signs that the cooler weather is affecting their joints.

We’re here to help. There are lots of options to help support joint health in our pets and we recommend discussing with you vet about which options are best for you and your pet.

If you’re noticing any changes in your pet,or just want to chat about how to keep them comfy this winter, give your local Vetora clinic a call. We’re always happy to help!

Pets

Heifers are home from grazing - is there liver fluke lurking?

From testing over the years we have found Liver fluke infection in grazing heifers, particularly from the King Country and areas where cattle graze on wet marshy pastures and margins of streams. The problem is that once infected, the adult fluke will live for years in your cows.

Often the first indication will be the presence of liver fluke on the killing sheet from cull cows. These are usually old flukes that have been living in the liver since they were grazing heifers.

Low levels of liver fluke cause decreased fertility, increased susceptibility to other diseases and parasites as well as decreased weight gain in growing cattle, and decreased milk production.

If you would like to know if you have an active infection in your heifers, a blood test from a group of animals will provide the answer.

Controlling fluke requires a flukacide and these drugs have a significant milk withhold so treatment needs to be carried out well before calving.

Drenching with Flukecare + Se is the most effective treatment, killing adult and immature fluke, BZ sensitive intestinal worms and four weeks of Selenium supplementation. It has a milk withholding of 35 days and meat and bobby calves of 28 days.

Alternatively, Ivomec Plus injection is effective in the control of adult fluke as well as mectin sensitive intestinal parasites and lungworm, as well as aiding in the control of lice. It has a milk withholding of 14 days and meat and bobby calves of 28 days.

https://nz.virbac.com/products/parasiticides-drenches/flukecare-plus-se#image

Farming

Abscesses in cows are localised, pus-filled infections that can develop due to injury or infection, or bacteria entering the body through open wounds or compromised skin. An abscess is a defence mechanism that helps prevent the spread of infection to other parts of the body. Abscesses have a wall, or capsule, that is formed by adjacent healthy cells in an attempt to keep the pus from infecting neighbouring structures. However, this capsule will also prevent immune cells and antibiotics from reaching the bacteria in the abscess.

Abscesses usually appear as firm, swollen lumps, often found around the neck, shoulder, flank or the back of the legs, but can occur on almost any part of the body. They may start small but can grow rapidly. It is not uncommon to see an abscess the size of a football, containing upwards of five litres of pus.

Many cows with abscesses appear otherwise healthy, but, if left untreated, an abscess is likely to cause discomfort, disrupt milk production, and even lead to systemic infection.

The most important aspect of treatment involves lancing and draining the abscess, ideally by a veterinarian. An X-shaped hole is recommended to prevent the wound sealing shut too early, which could allow the abscess to fill up again. Where possible, the hole should be located to enable it to drain freely via gravity, and it should be big enough to insert a finger into the abscess to allow exploration for foreign bodies (sticks, bits of wire, pieces of bone, etc) or pieces of firm pus or necrotic tissue that can block the hole and impede drainage.

The abscess should be thoroughly flushed, ideally with dilute iodine or chlorhexidine, but if drainage of the abscess is good, tap water will be ok.

I would strongly recommend administering local anaesthetic before lancing an abscess, as it is necessary to make more than one cut through thick cow skin, sometimes also through muscle, as well as through the abscess capsule. Although the area is under pressure from the abscess, this will still be a painful procedure for the cow. An anti-inflammatory, such as Metacam or Ketomax, may also be given to provide further pain relief and help reduce inflammation and swelling at the abscess site. Antibiotics are usually not given due to the abscess capsule.

The abscess should continue to be flushed out for a further two to five days, and during this time, it is good practice to continue to explore the hole with a gloved finger to search for any objects that could contribute to the infection, or that may block the drainage hole.

Preventing abscesses can be difficult, but if there is an outbreak of abscesses with a common location, consider investigating broken gates and rails, faulty equipment, and injection hygiene and technique.

Regularly inspecting cows for signs of injury or infection is crucial, as early detection leads to easier treatment.

Farming

Warning:

A dry autumn significantly increases the risk of lethal nitrate poisoning outbreaks. Spikes in nitrate levels often occur in seasons like the one we are experiencing when seasonal conditions combine in the autumn and winter, particularly following summers and autumns that are drier than normal as rapid uptake of nitrate from the soil by plants occurs with rains following drought conditions. Nitrate levels then build up in pasture when nitrate is taken up by the plant faster than it can be converted into protein.

This can be due to deficiency in plant energy due to plant stress or low sunlight levels, especially in annual grasses and crops with a high nitrate demand. Nitrates can be absorbed quickly by plants when temperatures are low, but conversion to protein occurs very slowly during cold weather causing nitrates to accumulate. The nitrate converts to nitrite in the rumen and then binds to haemoglobin in the blood stopping it from carrying oxygen. Death can occur rapidly due to lack of oxygen to the brain.

Signs of poisoning include muscle tremors staggering and collapse but animals are often found dead. Mucus membranes and teats have a distinctive bluish chocolate colour and blood looks like dairy milk chocolate.

Surviving animals will often abort due to lack of oxygen to the foetus. To reduce the risk of poisoning cattle should not go onto newly sown pasture hungry and should have been fed something high in fibre e.g. hay or silage prior to grazing Introduce stock to high risk paddocks in the early afternoon so that plants have had the sunlight necessary to convert excess nitrate to protein. Warm, dull and overcast days will be more dangerous.

Do not leave on risky pasture overnight. Restrict grazing time to around 1 hour and control the area they have access to. Give time to adjust to the feed by gradually increasing the intake. (This gives time for the rumen microflora to adjust). Check cattle regularly for signs of poisoning. It usually takes 4-5 hours for signs to develop.

To ensure your herbage is safe can test your herbage with a nitrate test kit available from your clinic or we can test it for you. We can help by treating affected cattle with methylene blue, so if you are suspicious of nitrate poisoning or have down cows or young stock after grazing new pasture please call us immediately as time will be of the essence!

Farming

KENNEL COUGH ALERT – What every dog owner should know

CANINE INFECTIOUS TRACHEOBRONCHITIS aka “KENNEL COUGH”

What is it?

Kennel cough is a viral disease similar to the dog “flu” which can be caused by multiple different viruses and bacteria. The kennel cough vaccination your dog gets protects against some of these viruses but not all so even if they are vaccinated, they can still get the cough if another virus is going around, but often they will have milder signs.

How can my dog get it?

Kennel cough is often caught when at doggy daycare, at the groomers or around other dogs, but they still can pick it up just from walking past another dog as it is spread by small droplets from sick dogs that cough and sneeze.

Even if your dog has contracted kennel cough, they may not show any signs until 10 days after the contact. And the cough itself can last up to 2 weeks!

What does it look like?

A sudden dry hacking cough

Retching and gagging, even bringing up foam

Being “off” and a bit lethargic

Runny nose and loud snorting / sneezing

It is most important to protect young and old dogs, and this is when it can become complicated with pneumonia.

When should you come to see us?

Kennel cough can be mild and your dog may clear the virus with some TLC, however, secondary inflammation can cause a lot of discomfort and can result in your pup feeling unwell. If you think your dog may have kennel cough, please contact your clinic to assess if he or she needs to be seen.

Please DO NOT come into the clinic when you arrive, wait in your car and call us to let us know you are there.

If you want to know more, give your closest Vetora clinic a call!

Pets

We were called out to perform a postmortem on a cow that had died suddenly despite showing no symptoms prior to this. This was the second cow this had happened to, and the farmer was concerned about a serious underlying problem in the herd.

Following a thorough, systematic approach we checked the cow from nose to tail trying to find the underlying cause. We started to get concerned as everything appeared completely normal… that was, until we cut into the heart and a large spurt of pus glazed my wet weathers! This cow had a large abscess INSIDE her heart muscle!

An intramyocardial abscess. These are extremely rare and occur when bacteria make it into the blood and establish themselves inside the heart muscle. It is likely that the cow had a minor underlying infection somewhere previously, allowing the bacteria to enter the bloodstream. In this case, the abscess likely just got so large that it disrupted the electrical conduction in the heart, ultimately resulting in a heart attack. This was likely an isolated event, and we found no evidence that this presented a threat to the herd.

Farming

The answer to the question of when to dry cows off depends on your plan for winter feeding and the trade-off between production this season and next season. Having said that, the rule of thumb is :

There are a couple of tools available to help guide your decision beyond the rules of thumb:

1. Infovet dry-off planning report

2. DairyNZ milk on/dry off tool (https://www.dairynz.co.nz/tools/milk-on-dry-off/#)

Talk to your vet or local DairyNZ area manager if you would like help to use this tool.

Farming

Here is your Vetora mid-April - Spring calving e-Update

Lovely to see some rain finally after a record breaking autumn drought! Spore counts are still reasonably high and with the rain may increase, so don’t relax on the zinc just yet – those spores are tough little sods and they don’t break down as quickly as you’d like them to, even with a few cooler nights.

COWS

HEIFERS

CALVES

All the best for the last few weeks of the season.

Farming

COWS

HEIFERS

CALVES

We are looking forward to catching up with everyone soon during RVM consults!

Farming

Recently one of our farmer members noticed a tiny sore spot on his finger. A swelling quickly spread to his wrist and forearm, so he saw his doctor who referred him to hospital where he was put on intravenous antibiotics.

Despite this it quickly got worse, and tests revealed antibiotic resistant bacteria in the wound. In the end the hospital was able to change to an effective antibiotic which made a big difference. However, due to complications and delayed treatment he required surgery and was off work for weeks

Antibiotic resistance is a significant global health threat. In 2019, it was directly responsible for approximately 1.3 million deaths worldwide and contributed to nearly five million deaths. Projections indicate the number will continue to increase.

Antibiotic resistance occurs in animals too, and the impact of antibiotics from animals entering the environment also impact on humans. A concerted effort is being made by vets to reduce the use of critically important or “red light” antibiotics that are the last line of defence for some human infections.

We also aim to use antibiotics to only treat infections as antibiotics are not indicated for preventing infections.

This is particularly important when using dry cow therapy. Most cows in a herd will have a cell count below 150,000 which indicates they are not infected and don’t need antibiotics.

Teat sealants like TeatSeal don’t contain antibiotic and stay in the cow for the long run to prevent mastitis through the longest dry period and that high-risk period at calving.

Talk to your vet at your annual dairy review about how they can work with you to reduce antibiotic use on your farm.

Farming

In the midst of a particularly hot Summer you may have noticed that your working day has gotten particularly sweaty over the past few months. Now if you add a black leather jacket and pants to your attire as well as a many-fold increase in water requirement you may have some idea of how a dairy cow in a Waikato Summer feels.

Heat stress occurs when a cow’s body is unable to regulate its temperature effectively due to hot weather and/or high humidity, leading to discomfort and physiological strain. Heat stress is generally due to high air temperatures, especially those above 25°C though other factors like humidity, direct exposure to sunlight and lack of ventilation can amplify the effects. Below is the Temperature Humidity Index (THI) which you can use to assess your herd’s risk of heat stress on a given day.

Heat stress may manifest in your herd as shade seeking, gathering at water sources, panting and drop in milk yield through to collapse and death in extreme cases. It is also a common cause of early abortion which explains some of the empty cows that never cycled again after mating that we find during summer scans.

So what can you do?

In this particularly hot Summer you will never fully combat the effects of heat stress but there is plenty you can do to help. Remember that if it’s hot for you, it’s hot for them!

Farming

Does your cat or dog get very anxious when visiting the vets? Here are a few pointers that may help reduce the stress for both you and your pet.

Dogs:

Call in to the clinic when not having a checkup to have staff give a treat to increase the times your dog comes without anything negative happening to them. Some dogs may be able to be examined in the car or car park – check with your clinic if this is possible on arrival.

DAP – dog appeasing pheromone can be purchased in the clinic to spray in the car on the way to the clinic.

Calmex tablets can be bought without a prescription to help mild cases of anxiety, just ask the reception staff as it is kept in our drug dispensary.

Anxiety medications – we can script out medications to give your dog an hour or two prior to their appointment to help take the edge off their anxiety. Examples include Gabapentin, Trazadone and Lorazepam at varying doses. Ask your vet about what “Chill protocol” is best for your dog.

Cats:

Feliway spray – this can be purchased in the clinic to spray into the car and cage on route to the clinic, or it can be used in a diffuser in a room the day before a visit.

Anxiety medication. Gabapentin capsules can be prescribed by a vet to be given the night before and the morning of an appointment to reduce anxiety.

If all else fails, we can sedate your pet on arrival to examine them for any painful procedure (nails, sore ears etc) or blood taking. If you think they may need to be sedated, do not feed them that morning as they will be required to have been fasted to safely sedate them.

Pets

Exciting Changes at Our Cambridge Clinic: A New Lunchroom and Revamped Cattery Suites!

February has arrived, and we couldn’t be more excited to share some great news – we’re in the process of creating a dedicated lunchroom for our team! This new addition has been long-awaited and will make a positive impact on our daily operations. To make room for the lunchroom, 10 of our single cattery suites have been removed, and this change will greatly improve both the work environment for our staff and the experience for our feline boarders.

With the new lunchroom, our hardworking team members will be able to enjoy uninterrupted breaks in a peaceful space. This will help them recharge during their busy shifts, without being disturbed by the usual hustle and bustle. We know how important it is for our staff to have that moment of quiet, and this change will allow us to create a more balanced environment. Plus, our lunching staff members won’t interrupt the veterinary team while they’re hard at work – it’s a win-win all around!

But that’s not all! We’re also thrilled to announce that we’ll be putting the remaining cattery suites through a transformation of their own. With a bit less floor space, we’re dedicated to ensuring that our boarding cats have an even better experience while staying with us. Our goal is to create an enriched environment that mimics the natural behaviors of cats, so they can feel at home and more engaged during their stay.

Some of the exciting upgrades to the cattery suites include:

Wall Scratching Plates: Cats love to scratch, and we want to provide them with plenty of options to express this natural behavior.

Additional Shelving: Cats are natural climbers, and by adding more shelves, we’ll give them even more places to perch, observe, and relax in comfort.

Connecting Cat Doors: For multi-cat bookings, we hope to have the ability to connect two single suites with a cat door, giving them a larger space to enjoy together.

We understand that every cat is unique, and we’re passionate about making sure they have the best possible experience with us. By creating a stimulating environment where they can engage in natural behaviors, our goal is for every feline guest to feel relaxed, happy, and entertained.

At our clinic, it’s always our priority to not only provide excellent care for our boarders but to also create a space where they can thrive. These changes reflect our ongoing commitment to ensuring your cats are as comfortable and content as possible.

We can’t wait to share the finished results with you, and as always, we look forward to welcoming your furry friends for their next stay with us!

Pets

A 12 year old greyhound recently presented to the Cambridge clinic in distress, after falling at home & crying in pain. The dog was incredibly agitated & panting. It was noticed that the patella (knee cap) had an unusual amount of movement & there was crepitus (crunching) when the stifle and hock were flexed. The thigh was swollen, so x-rays were taken and diagnosed a pathological fracture of the femur due to weakening of the bone from an osteosarcoma.

Osteosarcomas are an aggressive form of bone cancer that primarily affect large or giant breed dogs, such as greyhounds, rottweilers, and Saint Bernards. Osteosarcomas may be found in any bones, but typically develop in the long bones, such as the limbs (usually “away from the elbow and towards the knee”). Signs of osteosarcoma include pain, swelling, or limping in the affected limb. The condition is most common in middle-aged to older dogs, though it can occur in younger dogs as well.

The exact cause of osteosarcomas in dogs remains unclear, but genetic predisposition, rapid bone growth, and trauma are considered potential contributing factors. The cancer typically spreads (metastasises) to other parts of the body, particularly the lungs, making early detection crucial for improving prognosis.

Diagnosis can involve a combination of physical examination, x-ray, and biopsy to confirm the presence of cancerous cells.

On x-ray, a bone with an osteosarcoma will appear “moth-eaten”. This is due to a process called osteolysis, which is resorption of bone matrix, and is essentially the reverse process of bone growth and development.

This leaves the affected area of the bone weakened and therefore vulnerable to a “pathological fracture”. Treatment of osteosarcomas is usually limited to amputation of the affected limb, however development of new tumors in other areas of the skeletal system is unfortunately very common.

Pets

Cows:

Heifers:

Calves/R1s:

Farming

Youngstock are an investment in your future herd. It is likely that your well-grown heifer calves have now left the home farm for grazing. Whether this is with a grazier, or on your property, you need to ensure they are set up for reaching their goal of joining the herd at the required mature liveweight.

The first challenge after leaving the home farm is continuing to grow well through summer. Calves need a consistent supply of energy, protein and fibre in the right balance to grow optimally.

There are two main reasons that calves don’t grow adequately on pasture in summer. Either they are not receiving enough pasture, or the pasture available is not suitable quality for growth.

Offering quality pasture is particularly challenging over summer when both the protein and energy content of pasture declines. To receive enough protein and energy to grow, calves grazing dry stalky summer pasture would need to eat more than is physically possible. Protein is particularly important for youngstock to develop their skeletal frame size. Failure to provide enough protein to growing calves pre-puberty can stunt growth, and this is something that cannot be corrected by improved feeding post-puberty.

Why does this matter? To achieve good reproduction in heifers, the target is to reach 60 percent of mature liveweight by mating time. A 500kg cow would need to average 700 grams per day from birth to achieve her mature weight.

Knowing the likely challenges heading into summer, declining growth rates and pasture low in energy and protein, what can we do to minimise the impacts?

As pasture quality decreases during the summer, closely monitor the pasture available. Consider other options like grass silage and well-balanced calf meals as supplements. High temperatures can reduce feed intake, so ensure calves have access to shade and cool clean water to help them cope with the heat. Weighing calves every 4 to 6 weeks to ensure they are meeting their target liveweights and identify drops in weight gains allows for early intervention. Prevent health challenges with strategies against parasites, facial eczema and trace element deficiencies.

Lifestyle

Farming

Don’t get burnt this summer!

With spore counts rising and the risk of facial eczema growing it’s important to consider purchasing your Faceguard now!

Faceguard is an elemental zinc bolus that provides up to 6 weeks protection from facial eczema in a single treatment. A further half dose delivered after 6 weeks will give you an additional 4-week cover. 10 weeks total coverage!!

There is a complete range that includes flexible treatment options for cattle ranging from 90-250kg and 251-660kg. This means the range allows treatment of calves of 90kg right up to adult cattle and bulls of 660kg.

Flexibility- Individual animal dosing is much more reliable than any trough/pasture treatment. Easy convenient dosing for all Cattle sizes from 90 – 660kgs

Longevity – A single application lasts up to 6 weeks with the option of topping up to give additional cover in a longer season.

Durability – Try as you must, but the boluses will not break when dropped!

REMEMBER - If you are bolusing on a hot sunny day leave the boluses in their polystyrene packaging with lids on as direct sunlight can soften them.

Please be careful whenever bolusing animals, whether it is zinc, trace mins, magnesium or Rumensin – we see throat injuries every year which could be avoided. Remember, don’t force it! Take your time and take breaks, it is not a fun job we know.

If you would like a hand treating your animals consider booking one of our technicians, we are more than happy to help!

Lifestyle

Farming

Sometimes you have to leave to realise that there is no place like home!

Having just returned from a two year working holiday in England, I don’t have many NZ relevant case studies for this time of year. I do have a plethora of photos of the variety of animals I saw while working in North Yorkshire. I apologise if you were hoping for an in-depth article on cancer eyes.

Sheep were a major portion of my work, the variety of breeds within the small area where I worked was impressive. From the dale-bred Mules, local Teeswaters, and rare breed Ryedales; it seemed like every second farmer had a unique breed of sheep!

Dairy practice is quite different as most of the dairy herds are housed and on a total mixed ration. Many of the farms had milking robots to reduce staff requirements. Some farms even had robots for pushing up feed and cleaning yards. Year-round calving meant you could calve a cow and then turn around and be presented with a late lactation sick cow at the same visit. Vaccination recommendations and animal health protocols made up a large portion of the vets work, especially for the high input/high output herds.

A large proportion of beef herds (suckler cows in English lingo) meant lots of caesarians in spring! There were some calls I turned up to where the cow was clipped and prepped for surgery before I even got there. The largest was a 74kg calf that had to be delivered with the help of 2-3 other people to lift the calf out of the side of the heifer.

While in the UK, I trained and was certified to TB test cattle and buffalo. Buffalo are very similar to cattle in terms of husbandry and disease, they are just more stubborn and tend to sit down when they don’t want to move. You can imagine how annoying that is when trying to move them through a crush.

Living overseas and working with a new system of farming was an excellent learning experience. UK farmers and vets are very good at monitoring disease status and using vaccination to reduce the number of cases and severity of disease. Some of this is not directly applicable to NZ, but it has helped me to think more critically about how and why we do what we do.

As well as deepening and widening my understanding, it has also increased my appreciation for NZ! There are many benefits to being an island, biosecurity being one of the biggest. Diseases like Louping ill, Anthrax, Bluetongue and Brucella are rare or exotic and mostly we don’t have to worry about them.

Farming

COWS

Plan for pregnancy testing – Six weeks after the last mating is the earliest that empties can be called. Please book your scan in early so we can give you the date and time of your choice. Most farms will need 2 scans for accurate ageing of all cows (the window is 40 to 90 days pregnant). After 100 days pregnant the accuracy of aging decreases. Make sure ear tags are clear & readable, replace any missing tags, and sort out any MINDA queries, double-up cow numbers, etc, to make the scanning day smoother and to make sure the information flows correctly when synchronising into Infovet.

The facial eczema season is coming – the best way to know if you need to start zinc is to bring in some grass so we can perform a spore count for your own farm. A week after you start providing the cows with the full recommended dose of zinc, you should check to see if the cows are actually getting this zinc at a therapeutic level, by either blood testing 10-15 cows, or doing a bulk milk zinc test. The cows must get zinc at the correct level, or they will not be protected against facial eczema (and you are wasting your money).

BMSCC is starting to increase for some – we have several trained mastitis assessors within the clinics to help keep a lid on it. Some milk cultures are a good place to start, along with a Mastitis Warrant of Fitness.

Plan your autumn-calving drying off – work out timings to allow for any dry cow withholdings and remember to order product early.

HEIFERS

Pregnancy testing heifers is important. Heifers, too, can be pregnancy tested from as early as six weeks after removing the bull. Keep a watch for any early abortions – diagnosis of a cause usually requires both blood from the heifer and fresh aborted material.

Have a summer feed plan with your grazier in case feed gets short – everyone likes to know so they can help early on rather than seeing under-sized animals returning home.

CALVES

Get them ready for grazing, and let the grazier know their status: lepto / 5 in 1 / BVD vax / last drench / last mineral treatments (copper capsule, B12/Selenium injection) so they can carry on after your hard work rearing them through spring. We have Animal Health Arrival/Departure cards which can capture this information for the grazier.

Weight gain and growth is key. Regular weighing will help identify those that are struggling and will allow targeted feeding or other interventions to make sure none are falling behind.

Lepto vaccinations are continuing: 4 – 6 weeks in between first and second ( + BVD + Salmonella…).

There's been a couple of pink eye cases in calves, outbreaks can occur if it's not dealt with promptly. The pinkeye vaccine is not available at the moment, so early detection and treatment is key.

Look after yourselves in the sun (when it’s out!), and hopefully you each enjoy a break off farm at some point.

Have a wonderful Christmas and New Year!

Farming

Lameness in our dairy herds is a persistent and consistent problem for most. Lameness can be reduced with excellent stockmanship, but is it fair enough to say we will never be without lame cows?? I think so.

So, if lameness is going to be a persistent problem, then the way we treat lame cows is very important. It’s imperative to identify lame cows early, effectively treat them, and minimise their time out of the main milking herd.

Also, is it safe to say that no one “loves” doing lame cows?? I don’t mind it, I find it satisfying to relieve the pain from the cow, but I’m not going to say that I love it. This emphasises the importance of having a simple and efficient process for treating lame cows. This is my process:

And…. That’s about it for most cases.

Some helpful tips:

Please give us a call at the clinic if you want us to give a demonstration to your staff on some of your lame cows.

Farming

‘A cow with long hooves or lameness drains every farmer’s finances. I frequently share this advice with my clients: neglecting hoof care leads to adverse financial results. No calculator can show positive numbers when it comes to lame cows.’ (Koos Vis, Diamond Hoof Care)

As an industry, our ultimate responsibility to dairy animals is their welfare, and this is non-negotiable. It is a bonus that we also make better profits.

Our challenge is to resist willful blindness – if you cannot decide if a cow is lame or not, then she is lame. When it is obvious and she is limping, we are days late in detection.

The hoof wall grows about 5cm per year. The inner and outer claws generally wear away at a different rate which leads to some areas being higher as the hoof changes shape. This changes hoof angle and weightbearing, leading to strain and damage to both hoof and limb. Comparable to us wearing odd shoes and walking on our heels.

There are three bones in each claw in the hoof, equivalent to our toe.

‘Teetering on their tiptoes like a 600kg ballerina is no mean feat for our wonderful cows.’ Tomas James, LLM UK

The discomfort of long claws reduces feed intake even in the face of adequate rations. When feed is tight, she cannot harvest sufficient nutrients to maintain either milk production or body condition. Down goes your profit, up goes your workload, down goes your morale, up goes your costs.

If we continue to turn a blind eye, the compromised hoof is likely to break apart with white line disease and sole ulcers. More misery for cow and staff, more work and cost for less return; dramatic plunge in profit.

I recently visited a mixed age cow whose gait was getting so slow she could barely get to the shed before milking was over. The photos below demonstrate just how overgrown her toe had become.

Because we didn’t have access to a handling crush with supportive limb and belly belts, the first trimming aimed to debulk the claws. This kept the time on three legs to a minimum so that she could cope with the discomfort to her hoof, hock, stifle and hip joints. Furthermore, tying the leg to rails invariably impedes access with both knife and grinder, making the work slow and laborious. Hoof trimming is an art best done with good light and 100% access to all parts of the claw, for both trimming decisions and assessment.

Once she settles into her ‘temporary feet’ we will return to further shape and optimise weightbearing of the wall, until she can grow out new hooves and restore limb posture.

Farming

COWS:

YEARLINGS:

CALVES:

https://www.vetora.co.nz/news-and-resources/grazing-departure-form

https://www.vetora.co.nz/news-and-resources/grazing-arrival-form

All the best for the rest of mating.

Farming

In late November last year, on an otherwise quiet weekend on duty I received a rather alarming call out during the middle of afternoon milking for multiple cows down on the yard and race. Any herd level event with collapsed cows is considered a high priority emergency, and is often associated with feed or toxicity.

Upon arrival I found the shed was going, and cows were walking out the exit race without much fuss, but they appeared twitchy and stiff legged. Cows rowed up for milking appeared fine from a distance, but on closer inspection had a subtle head bob that worsened when they turned their heads towatch me. The herd had been absolutely fine in the morning, but in trying to get them to the shed this afternoon some would intermittently fall over on the race and be unable to rise. The same happened on the yard when the backing gate was put on, or when cows pushed to exit the shed. If left alone for long enough the down cows would eventually rise under their own steam and carry on like nothing had happened.

All of this together indicates a simple, but frustrating disease we more commonly see in calves – Ryegrass staggers. Not to be confused with grass staggers (which is caused by low magnesium) ryegrass staggers is caused by a toxin called Lolitrem B, and is characterised by an intention induced tremor. This means that the faster an animal tries to move, the worse the tremors become, but an animal standing still in a paddock will have next to no clinical signs of the disease.

Lolitrem B is produced by a fungal endophyte in many ryegrass pastures. The endophyte is included to reduce insect damage to growing pasture, and the toxin it produces is most highly concentrated in the base of the leaf sheath and in the flower heads. The toxin has no long lasting effecton the nervous system, and once removed from the unsafe pasture cows will return to normal fairly quickly. Most of the damage to stock with this disease process comes from misadventure – animals fall into drains or fences and are unable to get out.

Unfortunately, there is also no easy fix for ryegrass staggers except for removing the source of exposure, which is difficult in a pasture-based system! Affected animals should be moved to new pasture and should not be allowed to graze close to the base of the sward. Increasing the supplement on offer will reduce the amount of pasture eaten.

In any affected mob, move animals slowly and gently, and plan for longer milking and walking times. Frustration is never a good mix with moving stock, but with ryegrass staggers in particular it will only make the ob harder. If cows go down, especially on concrete, the best option is to move away, leave them undisturbed, and allow them to rise in their own time.

Farming

Broadly speaking, mastitis in New Zealand is separated into two groups: environmental and contagious. While the majority of cases throughout the season are from environmental sources, contagious mastitis bugs are also present and can become a major issue if not identified early on. Contagious mastitis is spread from cow to cow, often during the milking process where bacteria can sit on milker’s hands or inside the liners. The major contagious pathogen in New Zealand dairy herds is Staphylococcus aureus.

Clinical signs and disease process:

Clinically, Staph aureus mastitis occurs in many forms, ranging from the suddenly collapsed cow with black mastitis, to a chronic, low grade subclinical infection. Chronic infections are the most important cause for financial losses via reduced milk production, high somatic cell count (SCC), treatment costs, and/or culling. Chronically infected cows also pose a major risk to other cows in the herd.

New infections with Staph aureus occur when uninfected quarters are exposed to infected milk. The bacteria multiply in milk ducts, leading to inflammation, blockage, and atrophy of the milk producing tissue. They can form fibrotic tissue and tiny abscesses, which are difficult to penetrate with antibiotic treatment. For this reason, Staph aureus infections tend to have a poor cure rate, and early identification and treatment is important.

Detection:

Culture has been the standard way to diagnose Staph aureus infection, however, an infected cow will only shed Staph aureus intermittently, with a peak in shedding pattern every 6.5 days. Because of this, a single culture has only a 74.5% probability of detecting Staph. This number will jump to 94 and 98% when culturing 2 and 3 samples, respectively.

Staph aureus screening can also be done during your herd test, using a test called PCR (polymerase chain reaction). Basically, the test is looking for the genetic material of the pathogen but has similar limitations as milk culture due to the intermittent shedding from an infected gland. When positive, there will be no doubt about the presence of infection. However, a single negative PCR result does not rule-out presence of “non-shedding” Staph. Approximately 70% of Staph positive cows will be identified by a single herd test.

StaphGold™ is an antibody test detecting the immune response to the Staph infection. The test has a sensitivity (true positive cows) of over 90% and the specificity (true negative cows) is very high (95%). Because this test looks for antibodies to Staph, rather than the bug itself, it is not affected by intermittent shedding.

Control and prevention:

Once a cow is identified positive, it is important that she is separated and milked last to avoid transmission to her herd mates. It is also important that all operators in the shed wear gloves. If treating, the cow should not be returned to the main milking mob until it is certain she has cleared the infection. Due to its poor cure rate and the risk to other cows in the herd, culling is often the best option for chronically infected cows.

Farming

Events that involve fireworks are a spectacular sight which most of us enjoy, unfortunately for many animals it can be a very distressing and stressful time. For our companion pets, livestock, zoo animals and wildlife fireworks can be unexpected and unpredictable. The loud bangs and bright flashes of light can be very scary and frightening.

Animals may be injured if they get too close to a lit firework or if the noise spooks them, they can run away, become disoriented and are then unable to find their way home, injuring themselves or even being involved in a traffic accident.

Here are a few ways to keep your animal safe and calm during firework celebrations

Pets

Waka – A two year old Huntaway working dog presented to our Otorohanga clinic with a harsh hacking cough and was finding it hard to bark and run without getting out of breath quickly. Waka normally loves herding the sheep and zooming around the farm, as a young dog he has lots of energy so naturally his owner was concerned about him.

When listening to Waka’s breathing with a stethoscope, the lungs sounded clear, but the trachea (windpipe) sounded harsh.

We sedated Waka so we could have a good look in his mouth/throat. Straight away we could see his epiglottis (this is the part that covers the trachea when the animal swallows and when it is open this allows air to pass from the mouth into the trachea) was swollen on the left side and covering over 60 percent of his airway. The left tonsil was also inflamed. No wonder poor Waka was so out of breath!

A needle was placed into the area where a fine needle aspirate was taken. This sample was examined under the microscope, where a lot of inflammatory cells and bacteria were seen.

This gave us a likely diagnosis of an abscess, possibly caused by eating bones that injured the throat on the way down.

Waka was prescribed antibiotics and anti-inflammatories and made a full recovery. He is back out on the farm chasing sheep and cattle, barking freely!

Pets

Catch up on the latest cases and information from our Small Animal team!

Pets

As veterinary surgeons we see cats for a variety of problems. A lot of these can be related to stress. Yes, our feline friends are very complex. Some of the well-known diseases that are stress-related are: blood in the urine, spraying, excessive grooming leading to furballs, bald patches and significant skin lesions; to name a few.

The good news is that for some cats all you have to do is improve your cat’s environment to make them happy. No medication, no diet changes.

To help you improve your cat’s environment there is a journal article, authored by feline behavioural specialists, on improving your cat’s home environment to make them happy.

Pets

Mating is upon us! Overall, most people’s cows were in good condition at calving and are milking well. Which is wonderful – but the downside is that the combination of rapid weight loss and high levels of milk production means that most people will have more non-cycling cows this season than they did last year.

Treat them early!

Things to put on the calendar for October:

COWS:

Share the link below with farm staff for a refresher: https://www.dairynz.co.nz/animal/reproduction-and-mating/heat-detection/observing-cows-to-detect-heats/

HEIFERS:

CALVES:

Hope the start of mating goes well for you all.

Farming

An oral combination drench of Eprinomectin, Oxfendazole and Levamisole with Selenium and Cobalt.

This 'new to the market' product is only available through veterinary practices and will lead the way in premium quality calf drenches.

This makes Turbo Triple Minidose the ideal treatment for routine worm control until calves reach a size that makes oral drenching difficult.

Turbo Triple Minidose offers key advantages of being a highly potent endectocide combination but with an improved safety profile when compared to an Abamectin based oral drench. It can be used in calves under 120kg body weight while also having an endectocide potency advantage over Ivermectin based oral combinations.

Eprinomectin is the most potent broad spectrum active – it can kill worms at lower concentrations of active in the animal. So, with the combination of Oxfendazole and Levamisole Turbo Triple Minidose is a major leap forward in triple active oral parasite control.

Key Benefits include:

- World first Eprinomectin, Levamisole and Oxfendazole oral calf drench

- More effective at delaying parasite resistance than single or double active products

- High Safety margin – can be used on calves under 120kg

- Developed for New Zealand conditions by a New Zealand owned company

- Includes the addition of Cobalt and Selenium

- Available in 1L, 5L and 20L packs

Turbo Triple Minidose is available at all Vetora clinics.

Farming